Stirner's critique of humane liberalism presents an eerie warning about the totalitarian ideologies, movements, and regimes of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. The ideologues and apparatchiki of the fascist, communist, and Islamic supremacist movements and regimes all learned that it is not enough to seize state power, private property, and subordinate markets to the demands of the “common good,” as they define it. Thanks to the theoretical contributions by intellectuals such as Antonio Gramsci and Georg Lukacs, totalitarians realized that they must also seize the “hearts and minds” of their subjects. Gramsci and Lukacs theorized that Marxism failed as a revolutionary ideology because it underestimates the importance of culture and consciousness in the revolutionary transformation of society and individuality. In practical terms, this means that revolutionaries must not only seize state power and confiscate private property, they must control as many forms of communication, cultural production, and symbolic interaction as possible. Those who witnessed history since the rise of the totalitarian states in the twentieth century, have seen the concrete meaning of “humane liberalism” and the consequences of the appropriation of property, particularity, and subjectivity on behalf of the state, society, and humanity. Stirner's warnings about the reduction of persons to ragamuffins or nullities anticipates the historical facts that appeared with the rise of the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, and continue in the totalitarian Islamic states and the consumerist welfare states. To the extent that contemporary science and philosophy function as propagandists for political, social, and humane liberalism, Stirner's exclusion from polite discourse becomes understandable.

--John F. Welsh, Max Stirner's Dialectical Egoism: A New Interpretation (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2010), 79n39.

Saturday, February 2, 2019

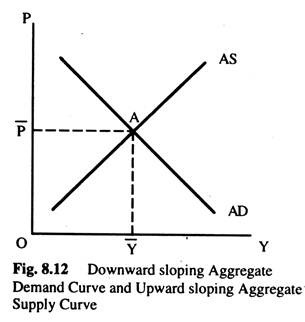

The AS / AD Model Is Logically Inconsistent; It Has Two Inconsistent Supply Analyses: One Implicitly Built into the Slope of the AD Curve, the Other Explicitly Behind the AS Curve

In short, the logical problem here is that one cannot derive an AD [aggregate demand] curve from the Keynesian model, because the Keynesian model includes a dynamic interactive effect between supply and demand in the form of the multiplier. The Keynesian model has embodied in it what Robert Clower (1994) calls Hansen's Law—the proposition that demand creates its own supply. This analysis of supply might be totally wrong, but there is no denying that the Keynesian model has assumptions of supply responses in it. As you move along the 45-degree line, supply is changing independently of any change in the wage/price ratio.

Given that the Keynesian model includes assumptions about supply, one cannot logically add another supply analysis to the model unless that other supply analysis is consistent with the Keynesian model assumption about supply. The AS [aggregate supply] curve used in the standard AS / AD model is not; thus the model is logically inconsistent. It has two inconsistent supply analyses: one implicitly built into the slope of the AD curve, the other explicitly behind the AS curve.

--David Colander, “The Stories We Tell: A Reconsideration of AS / AD Analysis,”Journal of Economic Perspectives 9, no. 3 (Summer 1995): 176.

Given that the Keynesian model includes assumptions about supply, one cannot logically add another supply analysis to the model unless that other supply analysis is consistent with the Keynesian model assumption about supply. The AS [aggregate supply] curve used in the standard AS / AD model is not; thus the model is logically inconsistent. It has two inconsistent supply analyses: one implicitly built into the slope of the AD curve, the other explicitly behind the AS curve.

--David Colander, “The Stories We Tell: A Reconsideration of AS / AD Analysis,”Journal of Economic Perspectives 9, no. 3 (Summer 1995): 176.

The Aggregate Supply / Aggregate Demand (AS / AD) Model Is Seriously Flawed. It Does Not Fulfill the Minimum Requirement of a Model: Logical Consistency

An Incorrectly Specified AD Curve

The logical specification problem concerns defining the AD curve that was derived from the Keynesian model. An appropriate definition of the AD curve derived from the Keynesian model would be as follows: The AD curve is the combination of points at which the Keynesian model is in equilibrium, given the relationship between price level and real output specified in the price-level thought experiment. The standard intro book does not give this definition; instead it gives a definition that parallels the definition of the partial equilibrium demand curve. A typical definition of an AD curve presented in an intro text is the following: Aggregate demand is a schedule, graphically represented as a curve, which shows the various amounts of goods and services that society as a whole will desire to purchase at various price levels, other things being equal. Notice that this definition parallels the definitions of the partial equilibrium demand curve, making appropriate distinctions between relative price and price level and quantity of a good and real output.

This textbook definition is a reasonable one of what the AD curve should be, although it is somewhat vague about what other things are being held constant. Typically, the explanation of what determines the slope of the AD curve, which focuses on the four effects discussed above, clarifies that everything except the direct effect of changes in the price level on output is being held constant.

The problem with this definition and delineation of what determines the slope of the AD curve is that it is not consistent with the derivation of the AD curve from the Keynesian model, because that Keynesian model–derived AD curve does not hold other things constant. The Keynesian model is quite explicitly a model of expenditures and production; it does not hold other things, specifically supply, constant.

--David Colander, “The Stories We Tell: A Reconsideration of AS / AD Analysis,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 9, no. 3 (Summer 1995): 174.

The logical specification problem concerns defining the AD curve that was derived from the Keynesian model. An appropriate definition of the AD curve derived from the Keynesian model would be as follows: The AD curve is the combination of points at which the Keynesian model is in equilibrium, given the relationship between price level and real output specified in the price-level thought experiment. The standard intro book does not give this definition; instead it gives a definition that parallels the definition of the partial equilibrium demand curve. A typical definition of an AD curve presented in an intro text is the following: Aggregate demand is a schedule, graphically represented as a curve, which shows the various amounts of goods and services that society as a whole will desire to purchase at various price levels, other things being equal. Notice that this definition parallels the definitions of the partial equilibrium demand curve, making appropriate distinctions between relative price and price level and quantity of a good and real output.

This textbook definition is a reasonable one of what the AD curve should be, although it is somewhat vague about what other things are being held constant. Typically, the explanation of what determines the slope of the AD curve, which focuses on the four effects discussed above, clarifies that everything except the direct effect of changes in the price level on output is being held constant.

The problem with this definition and delineation of what determines the slope of the AD curve is that it is not consistent with the derivation of the AD curve from the Keynesian model, because that Keynesian model–derived AD curve does not hold other things constant. The Keynesian model is quite explicitly a model of expenditures and production; it does not hold other things, specifically supply, constant.

--David Colander, “The Stories We Tell: A Reconsideration of AS / AD Analysis,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 9, no. 3 (Summer 1995): 174.

Friday, February 1, 2019

Virtually Every Aspiring Monopolist in the Country Tried to be Designated a "Public Utility," Including the Radio, Real Estate, Milk, Air Transport, Coal, Oil, and Agricultural Industries

Legislative "regulation" of gas and electric companies produced the predictable result of monopoly prices, which the public complained bitterly about. Rather than deregulating the industry and letting competition control prices, however, public utility regulation was adopted to supposedly appease the consumers who, according to Brown, "felt that the negligent manner in which their interests were being served [by legislative control of gas and electric prices] resulted in high rates and monopoly privileges. The development of utility regulation in Maryland typified the experience of other states."

Not all economists were fooled by the "natural monopoly" theory advocated by utility industry monopolists and their paid economic advisers. In 1940 economist Horace M. Gray, an assistant dean of the graduate school at the University of Illinois, surveyed the history of "the public utility concept," including the theory of "natural" monopoly. "During the nineteenth century," Gray observed, it was widely believed that "the public interest would be best promoted by grants of special privilege to private persons and to corporations" in many industries. This included patents, subsidies, tariffs, land grants to the railroads, and monopoly franchises for "public" utilities. "The final result was monopoly, exploitation, and political corruption." With regard to "public" utilities, Gray records that "between 1907 and 1938, the policy of state-created, state-protected monopoly became firmly established over a significant portion of the economy and became the keystone of modern public utility regulation." From that time on, "the public utility status was to be the haven of refuge for all aspiring monopolists who found it too difficult, too costly, or too precarious to secure and maintain monopoly by private action alone."

In support of this contention, Gray pointed out how virtually every aspiring monopolist in the country tried to be designated a "public utility," including the radio, real estate, milk, air transport, coal, oil, and agricultural industries, to name but a few. Along these same lines, "the whole NRA experiment may be regarded as an effort by big business to secure legal sanction for its monopolistic practices." Those lucky industries that were able to be politically designated as "public utilities" also used the public utility concept to keep out the competition.

--Thomas J. DiLorenzo, "The Myth of Natural Monopoly," Review of Austrian Economics 9, no. 2 (1996): 48-49.

Not all economists were fooled by the "natural monopoly" theory advocated by utility industry monopolists and their paid economic advisers. In 1940 economist Horace M. Gray, an assistant dean of the graduate school at the University of Illinois, surveyed the history of "the public utility concept," including the theory of "natural" monopoly. "During the nineteenth century," Gray observed, it was widely believed that "the public interest would be best promoted by grants of special privilege to private persons and to corporations" in many industries. This included patents, subsidies, tariffs, land grants to the railroads, and monopoly franchises for "public" utilities. "The final result was monopoly, exploitation, and political corruption." With regard to "public" utilities, Gray records that "between 1907 and 1938, the policy of state-created, state-protected monopoly became firmly established over a significant portion of the economy and became the keystone of modern public utility regulation." From that time on, "the public utility status was to be the haven of refuge for all aspiring monopolists who found it too difficult, too costly, or too precarious to secure and maintain monopoly by private action alone."

In support of this contention, Gray pointed out how virtually every aspiring monopolist in the country tried to be designated a "public utility," including the radio, real estate, milk, air transport, coal, oil, and agricultural industries, to name but a few. Along these same lines, "the whole NRA experiment may be regarded as an effort by big business to secure legal sanction for its monopolistic practices." Those lucky industries that were able to be politically designated as "public utilities" also used the public utility concept to keep out the competition.

--Thomas J. DiLorenzo, "The Myth of Natural Monopoly," Review of Austrian Economics 9, no. 2 (1996): 48-49.

The Identification of Inequality with Injustice and of Equality with Social Justice Have Become Characteristic of “the Socialists of All Parties”

Consider, for example, quotations from a Fabian Society review of the 1974-9 Labour Party administrations in the United Kingdom. The Editors proclaim “that the Labour Party can and should light a flame in a world of injustice and inequality.” Contributor after contributor speaks of “socialist canons of equality and social justice” and of “a more socially just and equal society”. One even goes so far as to lay it down — without attempting to explain what this might mean or why we should accept it as true — that, in particular, “Racial equality requires a society which is equal in all respects”.

Such identification of inequality with injustice and of equality with social justice have become characteristic of “the socialists of all parties”. According to Bosanquet and Townsend, these identifications were manifested in two ways. In the first place, none of the contributors made any attempt to respond to the request of the editors that they should examine and elucidate “the meaning of equality”. In the second place, and perhaps still more significant, the editors failed to demand, and the contributors neglected to offer, any reasons at all either for adopting equality as a value or for concluding themselves entitled or required to impose that value upon others by force. No doubt it appeared to one and all altogether obvious that a just society must be an equal one; if not perhaps, if this is conceivable, “a society which is equal in all respects”. For, given the equation between equality and justice, then there would certainly be no need for further justification on either count.

--Antony G. N. Flew, "Socialism and 'Social' Justice," Journal of Libertarian Studies 11, no. 2 (Summer 1995): 77-78.

Such identification of inequality with injustice and of equality with social justice have become characteristic of “the socialists of all parties”. According to Bosanquet and Townsend, these identifications were manifested in two ways. In the first place, none of the contributors made any attempt to respond to the request of the editors that they should examine and elucidate “the meaning of equality”. In the second place, and perhaps still more significant, the editors failed to demand, and the contributors neglected to offer, any reasons at all either for adopting equality as a value or for concluding themselves entitled or required to impose that value upon others by force. No doubt it appeared to one and all altogether obvious that a just society must be an equal one; if not perhaps, if this is conceivable, “a society which is equal in all respects”. For, given the equation between equality and justice, then there would certainly be no need for further justification on either count.

--Antony G. N. Flew, "Socialism and 'Social' Justice," Journal of Libertarian Studies 11, no. 2 (Summer 1995): 77-78.

The Basic Error, Begetting All Other Errors in the Marxian System, Consists in the Implicit Equivocation between Manual Labor and Wage Income

From the essentially correct fact that productive and purposive human labor is the primary means to transform nature-given resources into physical means to sustain and improve material conditions of human life and well-being, Marx, following Smith, impermissibly concludes that the wage income is the natural and primary income category of (manual) labor and that all other categories of income (profits, interest, dividends, rents) existing under capitalism are by necessity deductions from what naturally and rightfully should belong to the wage earners. And so, if it were not for the “appropriation of land and accumulation of stock” by a few, so Smith and Marx, the total value of products would exhaustibly be all wages and really belonged to the wage earners. The ascendancy of the marginal utility theory of value did not materially change this understanding. Reisman openly declares and provides a proof of his case that the Smith-Marx framework is actually fully in accord with the otherwise quite different positive theory of interest of Marx’s strongest 19th century critic—Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk. Böhm-Bawerk merely provided a strong critique of some aspects of Marx’s theory, not the whole of it. The legacy of Smith and Marx on the subject of profits/interest and wages continued to live on totally unchallenged even in the writings of Marx’s staunchest critics, including Mises, Hayek, and Rothbard.

What is wrong with Marx’s conceptual and substantive description of capitalist economic reality? The basic error, begetting all other errors in the Marxian system, consists in the implicit equivocation between manual labor and wage income.

It should be obvious that merely to work and produce things is not the same as to work for money and receive wages for the work performed. The two pairs are brought into a definite relation only if there is someone willing and able to invest the necessary money funds as wage payments. Furthermore, the more capital is invested in form of wage payments and/or acquisition of capital goods the greater is the extent of the division of labor, the greater is the productivity of labor and thus the higher will be the standard of living, above all of the wage earners. In no way can profit be attributable to the exploitation of labor (let alone manual labor) by capital and capital accumulation. To the contrary, with respect to the process of (nominal and real) income formation, Marx attaches to the accumulation of capital a role which is exactly opposite to the actual one.

--Wladimir Kraus, review of Capitalism: A Treatise on Economics, by George Reisman, Libertarian Papers 1, art. no. 14 (2009): 5-6.

What is wrong with Marx’s conceptual and substantive description of capitalist economic reality? The basic error, begetting all other errors in the Marxian system, consists in the implicit equivocation between manual labor and wage income.

It should be obvious that merely to work and produce things is not the same as to work for money and receive wages for the work performed. The two pairs are brought into a definite relation only if there is someone willing and able to invest the necessary money funds as wage payments. Furthermore, the more capital is invested in form of wage payments and/or acquisition of capital goods the greater is the extent of the division of labor, the greater is the productivity of labor and thus the higher will be the standard of living, above all of the wage earners. In no way can profit be attributable to the exploitation of labor (let alone manual labor) by capital and capital accumulation. To the contrary, with respect to the process of (nominal and real) income formation, Marx attaches to the accumulation of capital a role which is exactly opposite to the actual one.

--Wladimir Kraus, review of Capitalism: A Treatise on Economics, by George Reisman, Libertarian Papers 1, art. no. 14 (2009): 5-6.

Thursday, January 31, 2019

Monetarists Have Effectively Countered Keynesians on Many Fronts, but They Both Ignore a Capital Structure in Macroeconomics and Business Cycle Theory

A stocktaking of the modern alternatives to the Austrian theory suggests that capital-based macroeconomics may be due for a comeback. Conventional Keynesianism, whether in the guise of the principles-level Keynesian cross, the intermediate IS-LM, or the advanced AS/AD is formulated at a level of aggregation too high to bring the cyclical quality of boom and bust into full view. Worse, the development of these tools of analysis in the hands of the modern textbook industry has involved a serious sacrifice of substance in favor of pedagogy. Students are taught about the supply and demand curves that represent the market for a particular good or service, such as hamburgers or haircuts. Then they are led into the macroeconomic issues by the application of similar-looking supply and demand curves to the economy as a whole. the transition to aggregate supply and aggregate demand, which is made to look deceptively simple, hides all the fundamental differences between microeconomic issues and macroeconomic issues. While these macroeconomic aggregates continue to be presented to college undergraduates, they have fallen into disrepute outside the classroom. One recent reconsideration of the macroeconomic stories told to students identifies fundamental inconsistencies in AS/AD analysis.

Conventional monetarism employs a level of aggregation as high as, if not higher than, that employed by Keynesianism. While Milton Friedman is to be credited with having persuaded the economics profession--and much of the general citizenry--of the strong relationship between the supply of money and the general level of prices, his monetarism adds little to our understanding of the relationship between boom and bust. The monetarists have effectively countered the Keynesians on many fronts, but they share with them the belief that macroeconomics and even business cycle theory can safely ignore all considerations of capital structure.

--Roger W. Garrison, "Introduction: The Austrian Theory in Perspective," in The Austrian Theory of the Trade Cycle and Other Essays, ed. Richard M. Ebeling (Auburn, AL: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 1996), 21-23.

Conventional monetarism employs a level of aggregation as high as, if not higher than, that employed by Keynesianism. While Milton Friedman is to be credited with having persuaded the economics profession--and much of the general citizenry--of the strong relationship between the supply of money and the general level of prices, his monetarism adds little to our understanding of the relationship between boom and bust. The monetarists have effectively countered the Keynesians on many fronts, but they share with them the belief that macroeconomics and even business cycle theory can safely ignore all considerations of capital structure.

--Roger W. Garrison, "Introduction: The Austrian Theory in Perspective," in The Austrian Theory of the Trade Cycle and Other Essays, ed. Richard M. Ebeling (Auburn, AL: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 1996), 21-23.

The Only Task a Government Was Ever Supposed to Assume--of Protecting Our Life and Property--Our Caretakers Do Not Perform

After more than a century of compulsory democracy, the predictable results are before our very eyes. The tax load imposed on property owners and producers makes the economic burden even of slaves and serfs seem moderate in comparison. Government debt has risen to breathtaking heights. Gold has been replaced by government manufactured paper as money, and its value has continually dwindled. Every detail of private life, property, trade, and contract is regulated by ever higher mountains of paper laws (legislation). In the name of social, public or national security, our caretakers "protect" us from global warming and cooling and the extinction of animals and plants, from husbands and wives, parents and employers, poverty, disease, disaster, ignorance, prejudice, racism, sexism, homophobia, and countless other public enemies and dangers. And with enormous stockpiles of weapons of aggression and mass destruction they "defend" us, even outside of the U.S., from ever new Hitlers and all suspected Hitlerite sympathizers.

However, the only task a government was ever supposed to assume--of protecting our life and property--our caretakers do not perform. To the contrary, the higher the expenditures on social, public, and national security have risen, the more our private property rights have been eroded, the more our property has been expropriated, confiscated, destroyed, and depreciated, and the more we have been deprived of the very foundation of all protection: of personal independence, economic strength, and private wealth. The more paper laws have been produced, the more legal uncertainty and moral hazard has been created, and lawlessness has displaced law and order. And while we have become ever more helpless, impoverished, threatened, and insecure, our rulers have become increasingly more corrupt, dangerously armed, and arrogant.

--Hans-Hermann Hoppe, Democracy: The God That Failed; The Economics and Politics of Monarchy, Democracy, and Natural Order (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2011), 89-90.

However, the only task a government was ever supposed to assume--of protecting our life and property--our caretakers do not perform. To the contrary, the higher the expenditures on social, public, and national security have risen, the more our private property rights have been eroded, the more our property has been expropriated, confiscated, destroyed, and depreciated, and the more we have been deprived of the very foundation of all protection: of personal independence, economic strength, and private wealth. The more paper laws have been produced, the more legal uncertainty and moral hazard has been created, and lawlessness has displaced law and order. And while we have become ever more helpless, impoverished, threatened, and insecure, our rulers have become increasingly more corrupt, dangerously armed, and arrogant.

--Hans-Hermann Hoppe, Democracy: The God That Failed; The Economics and Politics of Monarchy, Democracy, and Natural Order (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2011), 89-90.

Wednesday, January 30, 2019

The Answer to the Question Why There Is Steadily Increasing Taxation Is This: A Dramatic Change in the Idea of Justice Has Taken Place in Public Opinion

On a highly abstract level the answer to the question why there is steadily increasing taxation is this: The root cause for this is a slow but dramatic change in the idea of justice that has taken place in public opinion.

Let me explain. One can acquire property either through homesteading, production, and contracting, or else through the expropriation and exploitation of homesteaders, producers, or contractors. There are no other ways. Both methods are natural to mankind. Alongside production and contracting there has always been a process of nonproductive and noncontractual property acquisitions. Just as productive enterprises can develop into firms and corporations, so can the business of expropriating and exploiting occur on a larger scale and develop into governments and states. That taxation as such exists and that there is the drive toward increased taxation should hardly come as a surprise. For the idea of nonproductive or noncontractual appropriations is almost as old as the idea of productive ones, and everyone—the exploiter certainly no less than the producer—prefers a higher income to a lower one.

The decisive question is this: what controls and constrains the size and growth of such a business?

It should be clear that the constraints on the size of firms in the business of expropriating producers and contractors are of a categorically different nature than those limiting the size of firms engaged in productive exchanges. Contrary to the claim of the public choice school, government and private firms do not do essentially the same sort of business. They are engaged in categorically different types of operations. . . .

With public opinion rather than demand and cost conditions thus identified as the constraining force on the size of government, I return to my original explanation of the phenomenon of ever-increasing taxation as “simply” a change in prevailing ideas.

If it is public opinion that ultimately limits the size of an exploitative firm, then an explanation of its growth in purely ideological terms is justified. Indeed, any other explanation, not in terms of ideological changes but of changes in “objective” conditions must be considered wrong. The size of government does not increase because of any objective causes over which ideas have no control and certainly not because there is a demand for it. It grows because the ideas that prevail in public opinion of what is just and what is wrong have changed. What once was regarded by public opinion as an outrage, to be treated and dealt with as such, has become increasingly accepted as legitimate.

--Hans-Hermann Hoppe, "The Economics and Sociology of Taxation," in The Economics and Ethics of Private Property: Studies in Political Economy and Philosophy, 2nd ed. (Auburn, AL: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2006), 50-51, 57.

Let me explain. One can acquire property either through homesteading, production, and contracting, or else through the expropriation and exploitation of homesteaders, producers, or contractors. There are no other ways. Both methods are natural to mankind. Alongside production and contracting there has always been a process of nonproductive and noncontractual property acquisitions. Just as productive enterprises can develop into firms and corporations, so can the business of expropriating and exploiting occur on a larger scale and develop into governments and states. That taxation as such exists and that there is the drive toward increased taxation should hardly come as a surprise. For the idea of nonproductive or noncontractual appropriations is almost as old as the idea of productive ones, and everyone—the exploiter certainly no less than the producer—prefers a higher income to a lower one.

The decisive question is this: what controls and constrains the size and growth of such a business?

It should be clear that the constraints on the size of firms in the business of expropriating producers and contractors are of a categorically different nature than those limiting the size of firms engaged in productive exchanges. Contrary to the claim of the public choice school, government and private firms do not do essentially the same sort of business. They are engaged in categorically different types of operations. . . .

With public opinion rather than demand and cost conditions thus identified as the constraining force on the size of government, I return to my original explanation of the phenomenon of ever-increasing taxation as “simply” a change in prevailing ideas.

If it is public opinion that ultimately limits the size of an exploitative firm, then an explanation of its growth in purely ideological terms is justified. Indeed, any other explanation, not in terms of ideological changes but of changes in “objective” conditions must be considered wrong. The size of government does not increase because of any objective causes over which ideas have no control and certainly not because there is a demand for it. It grows because the ideas that prevail in public opinion of what is just and what is wrong have changed. What once was regarded by public opinion as an outrage, to be treated and dealt with as such, has become increasingly accepted as legitimate.

--Hans-Hermann Hoppe, "The Economics and Sociology of Taxation," in The Economics and Ethics of Private Property: Studies in Political Economy and Philosophy, 2nd ed. (Auburn, AL: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2006), 50-51, 57.

Inflation Puts a Brake on Social Mobility; the Rich Stay Rich (Longer) and the Poor Stay Poor (Longer) than They Would in a Free Society

This excessive production of money and money titles is inflation by the Rothbardian definition, which we have adapted in the present study to the case of paper money. Inflation is an unjustifiable redistribution of income in favor of those who receive the new money and money titles first, and to the detriment of those who receive them last. In practice the redistribution always works out in favor of the fiat-money producers themselves (whom we misleadingly call “central banks”) and of their partners in the banking sector and at the stock exchange. And of course inflation works out to the advantage of governments and their closest allies in the business world. Inflation is the vehicle through which these individuals and groups enrich themselves, unjustifiably, at the expense of the citizenry at large. If there is any truth to the socialist caricature of capitalism—an economic system that exploits the poor to the benefit of the rich—then this caricature holds true for a capitalist system strangulated by inflation. The relentless influx of paper money makes the wealthy and powerful richer and more powerful than they would be if they depended exclusively on the voluntary support of their fellow citizens. And because it shields the political and economic establishment of the country from the competition emanating from the rest of society, inflation puts a brake on social mobility. The rich stay rich (longer) and the poor stay poor (longer) than they would in a free society.

--Jörg Guido Hülsmann, Deflation and Liberty (Auburn, AL: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2008), 33-34.

--Jörg Guido Hülsmann, Deflation and Liberty (Auburn, AL: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2008), 33-34.

Credit Money Can Never Have a Circulation That Matches the Circulation of the Natural Monies because of the Risk of Default

As the name says, credit money comes into being when financial instruments are being used in indirect exchanges. Suppose Ben lends 10 oz. of silver to Mike for one year, and that in exchange Mike gives him an IOU (I owe you). Suppose further that this IOU is a paper note with the inscription “I owe to the bearer of this note the sum of 10 oz., payable on January 1, 2010 (signature).” Then Ben could try to use this note as a medium of exchange. This might work if the prospective buyers of the note will also trust Mike's declaration to pay back the credit as promised. If Mike's reputation is good with certain people, then it is likely that these people will accept his note as payment for their goods and services. Mike's IOU then turns into credit money.

Credit money can never have a circulation that matches the circulation of the natural monies. The reason is that it carries the risk of default. Cash exchanges provide immediate control over the physical money. But the issuer of an IOU might go bankrupt, in which case the IOU would be just a slip of paper.

Not surprisingly, therefore, credit money has reached wider circulation only when the credit was denominated in terms of some commodity money, when the reputation of the issuer was beyond doubt, and when it was the only way to quickly provide the government with the funds needed to conduct large-scale war. This was for example the case with the American Continentals that financed the War of Independence and with the French assignats that financed the wars of the French revolutionaries against the rest of Europe. In the early days, credit money had also been issued in other forms than paper. In particular, IOUs made out of leather have been repeatedly used as money starting in the ninth century.

Credit money is only a derived kind of money. It receives its value from an expected future redemption in some commodity. In this respect it crucially differs from paper money, which is valued for its own sake.

--Jörg Guido Hülsmann, The Ethics of Money Production (Auburn, AL: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2008), 28-29.

Credit money can never have a circulation that matches the circulation of the natural monies. The reason is that it carries the risk of default. Cash exchanges provide immediate control over the physical money. But the issuer of an IOU might go bankrupt, in which case the IOU would be just a slip of paper.

Not surprisingly, therefore, credit money has reached wider circulation only when the credit was denominated in terms of some commodity money, when the reputation of the issuer was beyond doubt, and when it was the only way to quickly provide the government with the funds needed to conduct large-scale war. This was for example the case with the American Continentals that financed the War of Independence and with the French assignats that financed the wars of the French revolutionaries against the rest of Europe. In the early days, credit money had also been issued in other forms than paper. In particular, IOUs made out of leather have been repeatedly used as money starting in the ninth century.

Credit money is only a derived kind of money. It receives its value from an expected future redemption in some commodity. In this respect it crucially differs from paper money, which is valued for its own sake.

--Jörg Guido Hülsmann, The Ethics of Money Production (Auburn, AL: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2008), 28-29.

It Is a Non-Sequitur to Conclude That Socialism’s Central Problem Is a Lack of Knowledge

Clearly, Hayek's thesis regarding the central problem of socialism is nonsensical. What categorically distinguishes socialism from firms and families is not the existence of centralized knowledge or the lack of the use of decentralized knowledge, but rather the absence of private property, and hence, of prices. In fact, in occasional references to Mises and his original calculation argument, Hayek at times appears to realize this, too. But his attempt to integrate his very own thesis with Mises's and thereby provide a new and higher theoretical synthesis fails.

The Hayekian synthesis consists of the following propositional conjunction: “Fundamentally, in a system in which the knowledge of the relevant facts is dispersed among many people, prices can act to coordinate the separate actions of different people” and “the price system” can serve as “a mechanism for communicating information.” While the second part of this proposition strikes one as vaguely Misesian, it is anything but clear how it is logically related to the first, except through Hayek's elusive association of “prices” with “information” and “knowledge.” However, this association is more of a semantic trick than rigorous argumentation. On one hand, it is harmless to speak of prices as conveying information. They inform about past exchange ratios, but it is a non-sequitur to conclude that socialism's central problem is a lack of knowledge. This would only follow if prices actually were information. However, this is not the case. Prices convey knowledge, but they are the exchange ratios of various goods, which result from the voluntary interactions of distinct individuals based on the institution of private property. Without the institution of private property, the information conveyed by prices simply does not exist. Private property is the necessary condition of the knowledge communicated through prices. Yet then it is only correct to conclude, as Mises does, that it is the absence of the institution of private property which constitutes socialism's problem. To claim that the problem is a lack of knowledge, as Hayek does, is to confuse cause and effect, or premise and consequence.

--Hans-Hermann Hoppe, "Socialism: A Property or Knowledge Problem?" in The Economics and Ethics of Private Property: Studies in Political Economy and Philosophy, 2nd ed. (Auburn, AL: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2006), 257-258.

The Hayekian synthesis consists of the following propositional conjunction: “Fundamentally, in a system in which the knowledge of the relevant facts is dispersed among many people, prices can act to coordinate the separate actions of different people” and “the price system” can serve as “a mechanism for communicating information.” While the second part of this proposition strikes one as vaguely Misesian, it is anything but clear how it is logically related to the first, except through Hayek's elusive association of “prices” with “information” and “knowledge.” However, this association is more of a semantic trick than rigorous argumentation. On one hand, it is harmless to speak of prices as conveying information. They inform about past exchange ratios, but it is a non-sequitur to conclude that socialism's central problem is a lack of knowledge. This would only follow if prices actually were information. However, this is not the case. Prices convey knowledge, but they are the exchange ratios of various goods, which result from the voluntary interactions of distinct individuals based on the institution of private property. Without the institution of private property, the information conveyed by prices simply does not exist. Private property is the necessary condition of the knowledge communicated through prices. Yet then it is only correct to conclude, as Mises does, that it is the absence of the institution of private property which constitutes socialism's problem. To claim that the problem is a lack of knowledge, as Hayek does, is to confuse cause and effect, or premise and consequence.

--Hans-Hermann Hoppe, "Socialism: A Property or Knowledge Problem?" in The Economics and Ethics of Private Property: Studies in Political Economy and Philosophy, 2nd ed. (Auburn, AL: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2006), 257-258.

Tuesday, January 29, 2019

The Acknowledgment of the Truth Contained in Say’s Law Was the Distinctive Mark of an Economist

Say emerged victoriously from his polemics with Malthus and Sismondi. He proved his case, while his adversaries could not prove theirs. Henceforth, during the whole rest of the nineteenth century, the acknowledgment of the truth contained in Say's Law was the distinctive mark of an economist. Those authors and politicians who made the alleged scarcity of money responsible for all ills and advocated inflation as the panacea were no longer considered economists but “monetary cranks.”

The struggle between the champions of sound money and the inflationists went on for decades. But it was no longer considered a controversy between various schools of economists. It was viewed as a conflict between economists and anti-economists, between reasonable men and ignorant zealots. When all civilized countries had adopted the gold standard or the gold-exchange standard, the cause of inflation seemed to be lost forever.

Economics did not content itself with what Smith and Say had taught about the problems involved. It developed an integrated system of theorems which cogently demonstrated the absurdity of the inflationist sophisms. It depicted in detail the inevitable consequences of an increase in the quantity of money in circulation and of credit expansion. It elaborated the monetary or circulation credit theory of the business cycle which clearly showed how the recurrence of depressions of trade is caused by the repeated attempts to “stimulate” business through credit expansion. Thus it conclusively proved that the slump, whose appearance the inflationists attributed to an insufficiency of the supply of money, is on the contrary the necessary outcome of attempts to remove such an alleged scarcity of money through credit expansion.

--Ludwig von Mises, "Lord Keynes and Say's Law," in Planning for Freedom: Let the Market System Work; A Collection of Essays and Addresses, ed. Bettina Bien Greaves (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2008), 97-98.

The struggle between the champions of sound money and the inflationists went on for decades. But it was no longer considered a controversy between various schools of economists. It was viewed as a conflict between economists and anti-economists, between reasonable men and ignorant zealots. When all civilized countries had adopted the gold standard or the gold-exchange standard, the cause of inflation seemed to be lost forever.

Economics did not content itself with what Smith and Say had taught about the problems involved. It developed an integrated system of theorems which cogently demonstrated the absurdity of the inflationist sophisms. It depicted in detail the inevitable consequences of an increase in the quantity of money in circulation and of credit expansion. It elaborated the monetary or circulation credit theory of the business cycle which clearly showed how the recurrence of depressions of trade is caused by the repeated attempts to “stimulate” business through credit expansion. Thus it conclusively proved that the slump, whose appearance the inflationists attributed to an insufficiency of the supply of money, is on the contrary the necessary outcome of attempts to remove such an alleged scarcity of money through credit expansion.

--Ludwig von Mises, "Lord Keynes and Say's Law," in Planning for Freedom: Let the Market System Work; A Collection of Essays and Addresses, ed. Bettina Bien Greaves (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2008), 97-98.

The Money Creation Process Made Possible by Fractional-Reserve Banking Is Not Financial Intermediation; It Is a Credit Creation Process

Money is a present good. As argued by Cochran and Call (1998),

--John P. Cochran, Steven T. Call, and Fred R. Glahe, "Credit Creation or Financial Intermediation? Fractional-Reserve Banking in a Growing Economy," Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics 2, no. 3 (Fall 1999): 54-55.

Money is the medium of exchange and is thus the present good par excellence. The implied household decision tree is: a. Present goods or future goods (save)? b. If present goods, specific consumption goods or money? Saving is the sacrifice of present goods (a claim on present goods is temporarily foregone) for a claim on future goods. Since the holding of cash balances, whether in the form of deposits or currency, does not require the sacrifice of present utility, changes in cash balances financed from current income are not a part of saving, but represent part of the allocation of income to provide present utility.Thus the proper economic interpretation of a deposit is that of a warehouse receipt. A deposit is a claim instrument, not a credit instrument. A bank deposit (redeemable at par on demand) is not a debt transaction. It is a bailment in its economic impact even if it is treated as a debt by the legal system. The money creation process made possible by fractional-reserve banking is not financial intermediation. It does not facilitate the transfer of savings to investors. Instead fractional-reserve banking and the associated money-creation process is a credit-creation process.

--John P. Cochran, Steven T. Call, and Fred R. Glahe, "Credit Creation or Financial Intermediation? Fractional-Reserve Banking in a Growing Economy," Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics 2, no. 3 (Fall 1999): 54-55.

Even a Democrat Accused FDR of Trying “to Transplant Hitlerism to Every Corner of this Country”

Perhaps not surprisingly, comparisons of the New Deal with totalitarian ideologies were part and parcel of the everyday rhetoric of Roosevelt's domestic enemies. A Republican senator at the time described the National Recovery Administration (NRA) as having gone “too far in the Russian direction,” while even a Democrat accused FDR of trying “to transplant Hitlerism to every corner of this country.” Herbert Hoover called for open resistance to FDR's policies: “We must fight again for a government founded on individual liberty and opportunity that was the American vision. If we lose we will continue down this New Deal road to some sort of personal government based upon collectivist theories. Under these ideas ours can become some sort of Fascist government.”

Such sentiments could, of course, be put down to the usual partisan politics and intraparty rivalries, were it not for the fact that they were echoed by intellectual observers of economics and social policies who were otherwise Roosevelt allies. They, too, saw a Fascist element at the core of the New Deal. Writing in the Spectator, liberal journalist Mauritz Hallgren noted:

Such sentiments could, of course, be put down to the usual partisan politics and intraparty rivalries, were it not for the fact that they were echoed by intellectual observers of economics and social policies who were otherwise Roosevelt allies. They, too, saw a Fascist element at the core of the New Deal. Writing in the Spectator, liberal journalist Mauritz Hallgren noted:

We in America are bound to depend more upon the State as the sole means of saving the capitalist system. Unattended by black-shirt armies or smug economic dictators--at least for the moment--we are being forced rapidly and definitely into Fascism. . . .Elsewhere, he observed:

I am certain that in this country it will come gradually, dressed up in democratic trappings so as not to offend people. But when it comes it will differ in no essential respect from the fascist regimes of Italy and Germany. This is Roosevelt's role--to keep people convinced that the state capitalism now being set up is entirely democratic and constitutional.In the North American Review, Roger Shaw concurred:

The New Dealers, strangely enough, have been employing Fascist means to gain liberal ends. The NRA with its code system, its regulatory economic clauses and some of its features of social amelioration, was plainly an American adaptation of the Italian corporate state in its mechanics. The New Deal philosophy resembles closely that of the British Labour Party, while its mechanism is borrowed from the BLP's Italian antithesis.--Wolfgang Schivelbusch, Three New Deals: Reflections on Roosevelt's America, Mussolini's Italy, and Hitler's Germany, 1933-1939 (New York: Picador Henry Holt and Company, 2007), Kobo e-book.

Monday, January 28, 2019

Free Competition Pitilessly Culls Out All Less-Productive Enterprises; the Private Entrepreneur Ruthlessly Abandons Enterprises That No Longer Pay

Most Social Democratic writers are quite silent on this point; others touch on it only incidentally. Thus, Kautsky names two methods that the future state will use for raising production. The first is the concentration of all production in the most efficient firms and the shutting down of all other, less high-ranking, firms. That this is a means of raising production cannot be disputed. But this method is in best operation precisely under the rule of free competition. Free competition pitilessly culls out all less-productive enterprises and firms. Precisely that it does so is again and again used as a reproach against it by the affected parties; precisely for that reason do the weaker enterprises demand state subsidies and special consideration in sales to public agencies, in short, limitation of free competition in every possible way. That the trusts organized on a private-enterprise basis work in the highest degree with these methods for achieving higher productivity must be admitted even by Kautsky, since he actually cites them as models for the social revolution. It is more than doubtful whether the socialist state will also feel the same urgency to carry out such improvements in production. Will it not continue a firm that is less profitable in order to avoid local disadvantages from its abandonment? The private entrepreneur ruthlessly abandons enterprises that no longer pay; he thereby makes it necessary for the workers to move, perhaps also to change their occupations. That is doubtless

harmful above all for the persons affected, but an advantage for the whole, since it makes possible cheaper and better supply of the markets. Will the socialist state also do that? Will it not, precisely on the contrary, out of political considerations, try to avoid local discontent? In the Austrian state railroads, all reforms of this kind were wrecked because people sought to avoid the damage to particular localities that would have resulted from abandonment of superfluous administrative offices, workshops, and heating plants. Even the Army administration ran into parliamentary difficulties when, for military reasons, it wanted to withdraw the garrison from a locality.

--Ludwig von Mises, Nation, State, and Economy: Contributions to the Politics and History of Our Time, trans. Leland B. Yeager, ed. Bettina Bien Greaves (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2006), 155-156.

harmful above all for the persons affected, but an advantage for the whole, since it makes possible cheaper and better supply of the markets. Will the socialist state also do that? Will it not, precisely on the contrary, out of political considerations, try to avoid local discontent? In the Austrian state railroads, all reforms of this kind were wrecked because people sought to avoid the damage to particular localities that would have resulted from abandonment of superfluous administrative offices, workshops, and heating plants. Even the Army administration ran into parliamentary difficulties when, for military reasons, it wanted to withdraw the garrison from a locality.

--Ludwig von Mises, Nation, State, and Economy: Contributions to the Politics and History of Our Time, trans. Leland B. Yeager, ed. Bettina Bien Greaves (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2006), 155-156.

Sunday, January 27, 2019

The Economic Failure of All Public Enterprises Is Not a Peculiarity of the Austrian Government; Public Enterprises Have Failed All Over the World

If one considers what enormous sums have been extracted from the nation’s wealth through the failure of publicly managed enterprises and through the failure of the Postal Savings Office, one can pretty well judge how completely different our national finances would be today if the national agenda were restricted to the more limited responsibilities of government. The economic failure of all public enterprises is, however, not a peculiarity of the Austrian government. Public enterprises have failed all over the whole world. The finances of every single European and non-European nation are in as much or greater disorder as the government concerned has gone farther into the field of the management of business enterprises. In view of this fact, it sounds like a mockery that only a few years ago the further expropriation of private enterprises was recommended in all earnestness for the relief of financial distress and that this policy is still looked upon by wide circles as the highest wisdom in financial policy. The real root of all of our finance difficulties lies precisely in the existence of these public enterprises; in order to cover their operational losses the private sector must be taxed enormously.

--Ludwig von Mises, "The Balance Sheet of Economic Policies Hostile to Property," in Between the Two World Wars: Monetary Disorder, Interventionism, Socialism, and the Great Depression, ed. Richard M. Ebeling, vol. 2 of Selected Writings of Ludwig von Mises (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2002), 238.

--Ludwig von Mises, "The Balance Sheet of Economic Policies Hostile to Property," in Between the Two World Wars: Monetary Disorder, Interventionism, Socialism, and the Great Depression, ed. Richard M. Ebeling, vol. 2 of Selected Writings of Ludwig von Mises (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2002), 238.

Property Taxes Impede the Creation of Capital; Capital Consumption Is Detrimental for both Property Owners and Workers

The second questionable principle is the preference for direct taxation—those taxes that are assessed on “property”—over indirect consumption taxes. Over many years, the inflammatory rhetoric of the Social Democrats has succeeded in spreading the view that taxes on commodities of mass consumption should be opposed, but that levying “taxes on property” does not affect the interests of the workers. The leaders of the Social Democratic party always talk about “gifts” for entrepreneurs whenever property-tax reductions are proposed. In reality the situation is quite the opposite. Property taxes impede the creation of capital. And when the taxation of enterprises goes too far, it results in the consumption of capital. To a large extent, this has been the case here in Austria for the last eighteen years. Capital consumption is detrimental not only for the owners of property but for the workers as well. The more unfavorable becomes the quantitative ratio of capital to labor, the lower is the marginal productivity of the work force, and, consequently, the lower are the wages that can be paid. That the Austrian economy is only able to compete and survive on the basis of the relatively low wages that are paid today is primarily due to the fact that very significant amounts of the capital belonging to Austrian entrepreneurs have been eaten up during the past eighteen years.

--Ludwig von Mises, "Adjusting Public Expenditures to the Economy's Financial Capacity," in Between the Two World Wars: Monetary Disorder, Interventionism, Socialism, and the Great Depression, ed. Richard M. Ebeling, vol. 2 of Selected Writings of Ludwig von Mises (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2002), 242-243.

--Ludwig von Mises, "Adjusting Public Expenditures to the Economy's Financial Capacity," in Between the Two World Wars: Monetary Disorder, Interventionism, Socialism, and the Great Depression, ed. Richard M. Ebeling, vol. 2 of Selected Writings of Ludwig von Mises (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2002), 242-243.

A Severe Economic Disease, Called “The Asset Price Inflation Virus,” Attacked the European Monetary Union

Why did European Monetary Union (EMU) enter existential crisis so soon after its creation According to the 'Berlin view' everything would have been fine if it had not been for a number of governments contriving to circumvent the strict fiscal discipline stipulated in the budget stability pact that accompanied the launch of the euro. The 'Paris and Brussels' view by contrast traces the crisis to a failure of the founding Treaty to provide for a fiscal, debt and banking union.

The leading hypothesis in this book puts the blame for the crisis and for the highly probable eventual break-up of EMU on the failure of its architects to build a structure which would withstand strong forces driving monetary instability whether from inside or outside. These flaws could have gone undetected for a long time. In practice though, very early in the life of the new union, the structure was so badly shaken as to leave EMU in a deeply ailing condition.

A severe economic disease, called 'the asset price inflation virus,' attacked EMU. The original source of the virus can be traced to the Federal Reserve, but the policies of the European Central Bank (ECB) added hugely to the danger of the attack. Serious inadequacies in Europe's new monetary framework meant that EMU had no immunity.

--Brendan Brown, Euro Crash: How Asset Price Inflation Destroys the Wealth of Nations, 3rd ed. (Houndmills, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), Kobo e-book.

The leading hypothesis in this book puts the blame for the crisis and for the highly probable eventual break-up of EMU on the failure of its architects to build a structure which would withstand strong forces driving monetary instability whether from inside or outside. These flaws could have gone undetected for a long time. In practice though, very early in the life of the new union, the structure was so badly shaken as to leave EMU in a deeply ailing condition.

A severe economic disease, called 'the asset price inflation virus,' attacked EMU. The original source of the virus can be traced to the Federal Reserve, but the policies of the European Central Bank (ECB) added hugely to the danger of the attack. Serious inadequacies in Europe's new monetary framework meant that EMU had no immunity.

--Brendan Brown, Euro Crash: How Asset Price Inflation Destroys the Wealth of Nations, 3rd ed. (Houndmills, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), Kobo e-book.

The Obama-Bernanke “Great Monetary Experiment” Was Designed to Drive Up Asset Prices and to Stop Price Deflation

The “Great Monetary Experiment” (GME) launched under the Obama Administration by its chosen Federal Reserve Chief Ben Bernanke was not the first in contemporary history. Indeed, since the Federal Reserve opened its doors, there has been a perpetual rolling out of monetary experiments, albeit the main officials in charge would never have agreed with that description. At most, they would have conceded that circumstances had forced them into monetary innovation, but this had not been their choice.

Those responsible for designing and implementing the GME had no such reticence. As we shall see in this volume, they were ready to gamble US and global prosperity on a set of theoretical propositions and innovatory tools as pioneered under their own chosen brand of neo-Keynesian economics. The justification for doing so was the darkness of the economic landscape in the immediate aftermath of the Great Panic (Autumn 2008) and their promise of an early dawn.

The big new idea in the Great Experiment was to “drive up asset prices” whilst simultaneously striving to prevent any whiff of price deflation appearing. “Quantitative Easing” was brandished as the magical tool. In fact, the experiment and the tool were not so new, and any transitory apparent effectiveness depended on a real life replay of the Emperor's New Clothes fable. As the real world theatre performance continued, many practical business decision makers remained anxious.

--Brendan Brown, introduction to A Global Monetary Plague: Asset Price Inflation and Federal Reserve Quantitative Easing (Houndmills, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), Kobo e-book.

Those responsible for designing and implementing the GME had no such reticence. As we shall see in this volume, they were ready to gamble US and global prosperity on a set of theoretical propositions and innovatory tools as pioneered under their own chosen brand of neo-Keynesian economics. The justification for doing so was the darkness of the economic landscape in the immediate aftermath of the Great Panic (Autumn 2008) and their promise of an early dawn.

The big new idea in the Great Experiment was to “drive up asset prices” whilst simultaneously striving to prevent any whiff of price deflation appearing. “Quantitative Easing” was brandished as the magical tool. In fact, the experiment and the tool were not so new, and any transitory apparent effectiveness depended on a real life replay of the Emperor's New Clothes fable. As the real world theatre performance continued, many practical business decision makers remained anxious.

--Brendan Brown, introduction to A Global Monetary Plague: Asset Price Inflation and Federal Reserve Quantitative Easing (Houndmills, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), Kobo e-book.

Experiments in Economic Crash Postponement: 1927/29 Versus 2016/18

History does not repeat, it echoes. At the time of writing (early 2018), it seems like there have been strong echoes in an “Indian summer phase” of global asset price inflation through late 2016, in the whole of 2017, and into early 2018, from Wall Street in the late 1920s. That earlier episode culminated in a devastating sequence of financial crashes. The danger of a repeat is widely evident, although the Federal Reserve has taken a crucially different policy step from back then. And in broader context, we should note that in the late 1920s, the world was barely ten years on from the World War I (a point emphasized to the author by Alex J. Pollock and also found in Kindleberger’s summing up of the causes of the Great Depression).

The echoes stem from an essential similarity in monetary circumstance. After the Great Recession of 1920–21, the recently created Federal Reserve (doors opened in 1914) embarked on a course of fighting “deflation dangers” whilst countering incipient cyclical downturns. Fed policy-makers were in part responding to contemporary criticism especially as voiced in Congress to the effect that their mismanagement had contributed to the severity of the Great Recession (too slow to halt inflationary policies once war ended and then excess zeal to bring prices down).

The technological revolution unfolding in the 1920s (mass assembly line, electrification, autos, radio, etc.) meant that prices had a natural and benign tendency to fall. The Fed, in resisting this, kept monetary conditions very easy, fostering a powerful asset price inflation which encompassed the market in stocks, real estate, and foreign loans (most of all to Germany). Similarly, in the aftermath of the 2000–02 economic downturn and equity market bust (led by Nasdaq), the Fed turned to “fighting deflation” despite a benign tendency at that time for prices to fall (economic weakness, globalization, a continuing productivity spurt reflecting the IT revolution). The fight against deflation was waged with much greater vigour following the 2007 panic and Great Recession despite a natural rhythm of prices downwards, now due to globalization, digitalization, and economic weakness, rather than any apparent productivity surge.

--Brendan Brown, The Case Against 2 Per Cent Inflation: From Negative Interest Rates to a 21st Century Gold Standard (Cham, CH: Springer International Publishing, 2018), 165-166.

The echoes stem from an essential similarity in monetary circumstance. After the Great Recession of 1920–21, the recently created Federal Reserve (doors opened in 1914) embarked on a course of fighting “deflation dangers” whilst countering incipient cyclical downturns. Fed policy-makers were in part responding to contemporary criticism especially as voiced in Congress to the effect that their mismanagement had contributed to the severity of the Great Recession (too slow to halt inflationary policies once war ended and then excess zeal to bring prices down).

The technological revolution unfolding in the 1920s (mass assembly line, electrification, autos, radio, etc.) meant that prices had a natural and benign tendency to fall. The Fed, in resisting this, kept monetary conditions very easy, fostering a powerful asset price inflation which encompassed the market in stocks, real estate, and foreign loans (most of all to Germany). Similarly, in the aftermath of the 2000–02 economic downturn and equity market bust (led by Nasdaq), the Fed turned to “fighting deflation” despite a benign tendency at that time for prices to fall (economic weakness, globalization, a continuing productivity spurt reflecting the IT revolution). The fight against deflation was waged with much greater vigour following the 2007 panic and Great Recession despite a natural rhythm of prices downwards, now due to globalization, digitalization, and economic weakness, rather than any apparent productivity surge.

--Brendan Brown, The Case Against 2 Per Cent Inflation: From Negative Interest Rates to a 21st Century Gold Standard (Cham, CH: Springer International Publishing, 2018), 165-166.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)