The case against patents can be summarized briefly: there is no empirical evidence that they serve to increase innovation and productivity, unless productivity is identified with the number of patents awarded—which, as evidence shows, has no correlation with measured productivity. This disconnect is at the root of what is called the “patent puzzle”: in spite of the enormous increase in the number of patents and in the strength of their legal protection, the US economy has seen neither a dramatic acceleration in the rate of technological progress nor a major increase in the levels of research and development expenditure.

Both theory and evidence suggest that while patents can have a partial equilibrium effect of improving incentives to invent, the general equilibrium effect on innovation can be negative. The historical and international evidence suggests that while weak patent systems may mildly increase innovation with limited side effects, strong patent systems retard innovation with many negative side effects. More generally, the initial eruption of innovations leading to the creation of a new industry—from chemicals to cars, from radio and television to personal computers and investment banking—is seldom, if ever, born out of patent protection and is instead the fruit of a competitive environment. It is only after the initial stage of rampant growth ends that mature industries turn toward the legal protection of patents, usually because their internal growth potential diminishes and they become more concentrated. These observations, supported by a steadily increasing body of evidence, are consistent with theories of innovation emphasizing competition and first-mover advantage as the main drivers of innovation, and they directly contradict “Schumpeterian” theories postulating that government-granted monopolies are crucial to provide incentives for innovation.

--Michele Boldrin and David K. Levine, "The Case Against Patents," Journal of Economic Perspectives 27, no. 1 (Winter 2013): 3-4.

Showing posts with label Journal of Economic Perspectives. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Journal of Economic Perspectives. Show all posts

Wednesday, May 1, 2019

Saturday, February 2, 2019

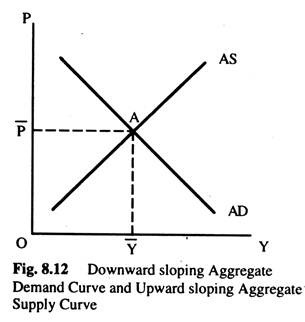

The AS / AD Model Is Logically Inconsistent; It Has Two Inconsistent Supply Analyses: One Implicitly Built into the Slope of the AD Curve, the Other Explicitly Behind the AS Curve

In short, the logical problem here is that one cannot derive an AD [aggregate demand] curve from the Keynesian model, because the Keynesian model includes a dynamic interactive effect between supply and demand in the form of the multiplier. The Keynesian model has embodied in it what Robert Clower (1994) calls Hansen's Law—the proposition that demand creates its own supply. This analysis of supply might be totally wrong, but there is no denying that the Keynesian model has assumptions of supply responses in it. As you move along the 45-degree line, supply is changing independently of any change in the wage/price ratio.

Given that the Keynesian model includes assumptions about supply, one cannot logically add another supply analysis to the model unless that other supply analysis is consistent with the Keynesian model assumption about supply. The AS [aggregate supply] curve used in the standard AS / AD model is not; thus the model is logically inconsistent. It has two inconsistent supply analyses: one implicitly built into the slope of the AD curve, the other explicitly behind the AS curve.

--David Colander, “The Stories We Tell: A Reconsideration of AS / AD Analysis,”Journal of Economic Perspectives 9, no. 3 (Summer 1995): 176.

Given that the Keynesian model includes assumptions about supply, one cannot logically add another supply analysis to the model unless that other supply analysis is consistent with the Keynesian model assumption about supply. The AS [aggregate supply] curve used in the standard AS / AD model is not; thus the model is logically inconsistent. It has two inconsistent supply analyses: one implicitly built into the slope of the AD curve, the other explicitly behind the AS curve.

--David Colander, “The Stories We Tell: A Reconsideration of AS / AD Analysis,”Journal of Economic Perspectives 9, no. 3 (Summer 1995): 176.

The Aggregate Supply / Aggregate Demand (AS / AD) Model Is Seriously Flawed. It Does Not Fulfill the Minimum Requirement of a Model: Logical Consistency

An Incorrectly Specified AD Curve

The logical specification problem concerns defining the AD curve that was derived from the Keynesian model. An appropriate definition of the AD curve derived from the Keynesian model would be as follows: The AD curve is the combination of points at which the Keynesian model is in equilibrium, given the relationship between price level and real output specified in the price-level thought experiment. The standard intro book does not give this definition; instead it gives a definition that parallels the definition of the partial equilibrium demand curve. A typical definition of an AD curve presented in an intro text is the following: Aggregate demand is a schedule, graphically represented as a curve, which shows the various amounts of goods and services that society as a whole will desire to purchase at various price levels, other things being equal. Notice that this definition parallels the definitions of the partial equilibrium demand curve, making appropriate distinctions between relative price and price level and quantity of a good and real output.

This textbook definition is a reasonable one of what the AD curve should be, although it is somewhat vague about what other things are being held constant. Typically, the explanation of what determines the slope of the AD curve, which focuses on the four effects discussed above, clarifies that everything except the direct effect of changes in the price level on output is being held constant.

The problem with this definition and delineation of what determines the slope of the AD curve is that it is not consistent with the derivation of the AD curve from the Keynesian model, because that Keynesian model–derived AD curve does not hold other things constant. The Keynesian model is quite explicitly a model of expenditures and production; it does not hold other things, specifically supply, constant.

--David Colander, “The Stories We Tell: A Reconsideration of AS / AD Analysis,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 9, no. 3 (Summer 1995): 174.

The logical specification problem concerns defining the AD curve that was derived from the Keynesian model. An appropriate definition of the AD curve derived from the Keynesian model would be as follows: The AD curve is the combination of points at which the Keynesian model is in equilibrium, given the relationship between price level and real output specified in the price-level thought experiment. The standard intro book does not give this definition; instead it gives a definition that parallels the definition of the partial equilibrium demand curve. A typical definition of an AD curve presented in an intro text is the following: Aggregate demand is a schedule, graphically represented as a curve, which shows the various amounts of goods and services that society as a whole will desire to purchase at various price levels, other things being equal. Notice that this definition parallels the definitions of the partial equilibrium demand curve, making appropriate distinctions between relative price and price level and quantity of a good and real output.

This textbook definition is a reasonable one of what the AD curve should be, although it is somewhat vague about what other things are being held constant. Typically, the explanation of what determines the slope of the AD curve, which focuses on the four effects discussed above, clarifies that everything except the direct effect of changes in the price level on output is being held constant.

The problem with this definition and delineation of what determines the slope of the AD curve is that it is not consistent with the derivation of the AD curve from the Keynesian model, because that Keynesian model–derived AD curve does not hold other things constant. The Keynesian model is quite explicitly a model of expenditures and production; it does not hold other things, specifically supply, constant.

--David Colander, “The Stories We Tell: A Reconsideration of AS / AD Analysis,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 9, no. 3 (Summer 1995): 174.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)